Basic Financial Concepts

Understanding the fundamentals of personal finance is crucial for building a secure financial future. This involves managing your income and expenses effectively, setting financial goals, and developing healthy saving habits. By mastering these basic concepts, you can take control of your finances and make informed decisions about your money.

Fundamental Principles of Money Management

Effective money management hinges on a few core principles. First, it’s vital to track your income and expenses meticulously. This allows you to understand where your money is going and identify areas where you can potentially save. Second, budgeting plays a critical role in allocating your resources effectively, ensuring that your spending aligns with your financial goals. Finally, consistent saving is paramount; it builds a financial safety net and enables you to achieve long-term objectives like buying a home or securing your retirement. These principles, when applied consistently, contribute significantly to financial well-being.

Income and Expenses Breakdown

Income represents the money you earn from various sources, such as your salary, investments, or side hustles. Expenses, on the other hand, are the costs associated with your day-to-day living and financial obligations. Categorizing your expenses – such as housing, transportation, food, and entertainment – provides a clear picture of your spending habits. Analyzing the relationship between your income and expenses helps determine your net income (income minus expenses), which is crucial for planning your savings and investments. For example, if your monthly income is $3000 and your monthly expenses are $2500, your net income is $500. This $500 can then be allocated towards savings, debt repayment, or investments.

The Importance of Budgeting and Saving

Budgeting is the process of creating a plan for how you will spend your money. A well-structured budget helps you control your spending, prioritize your financial goals, and avoid unnecessary debt. It provides a framework for allocating your income towards essential expenses, savings, and other financial objectives. Saving, on the other hand, involves setting aside a portion of your income regularly. This builds a financial safety net, allowing you to handle unexpected expenses or invest in your future. A consistent savings plan, even if it involves small amounts, can significantly contribute to achieving your long-term financial goals. For instance, saving 10% of your income consistently over several years can lead to substantial savings.

Simple Budgeting Template

A simple budgeting template can significantly aid in managing your finances. The following table provides a basic framework for tracking income and expenses. Remember to adjust categories and amounts to reflect your individual circumstances.

| Income Source | Amount | Expense Category | Amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salary | $2500 | Rent | $1000 |

| Investments | $200 | Groceries | $400 |

| Freelancing | $300 | Transportation | $200 |

| Entertainment | $100 | ||

| Total Income | $3000 | Total Expenses | $1700 |

| Net Income | $1300 |

Investing Fundamentals

Investing your money wisely can pave the way for long-term financial security and the achievement of your financial goals. Understanding the basics of investing is crucial before embarking on any investment journey. This section will explore fundamental investment strategies, the relationship between risk and return, and a comparison of common investment vehicles.

Investment Strategies for Beginners

A well-defined investment strategy is essential for beginners. Starting with a clear understanding of your financial goals and risk tolerance is paramount. Diversification, spreading your investments across different asset classes, is a key principle to mitigate risk. Dollar-cost averaging, a strategy of investing a fixed amount of money at regular intervals, helps to reduce the impact of market volatility. Finally, consistent investment over time, regardless of market fluctuations, is crucial for long-term growth.

Risk and Return in Investing

Investing inherently involves risk; the potential for loss is always present. However, higher potential returns often accompany higher levels of risk. This relationship is often visualized as a risk-return spectrum. Low-risk investments, like government bonds, typically offer lower returns, while high-risk investments, such as individual stocks in volatile sectors, have the potential for significantly higher – or lower – returns. A balanced portfolio, carefully constructed to align with your risk tolerance and financial objectives, is key to managing this trade-off effectively. For example, a young investor with a long time horizon might tolerate more risk than someone nearing retirement.

Stocks, Bonds, and Mutual Funds

Stocks represent ownership in a company, offering potential for high growth but also significant volatility. Bonds, on the other hand, are loans to companies or governments, generally considered less risky than stocks but offering lower potential returns. Mutual funds pool money from multiple investors to invest in a diversified portfolio of stocks, bonds, or other assets, offering diversification and professional management. The choice between these depends on individual risk tolerance, investment goals, and time horizon. For instance, a conservative investor might prefer bonds or low-risk mutual funds, while a more aggressive investor might allocate a larger portion of their portfolio to stocks.

Investment Options Comparison

| Investment Type | Risk Level | Potential Return | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government Bonds | Low | Low to Moderate | US Treasury Bonds |

| Index Funds | Medium | Moderate to High | S&P 500 Index Fund |

| Individual Stocks (e.g., Tech Stocks) | High | High to Very High (or Loss) | Shares of a rapidly growing technology company |

Banking and Financial Institutions

The financial system relies heavily on a network of banks and other financial institutions to facilitate the flow of money and credit throughout the economy. These institutions provide a range of services to individuals and businesses, playing a crucial role in savings, investments, and economic growth. Understanding their roles and functions is essential for navigating the financial landscape effectively.

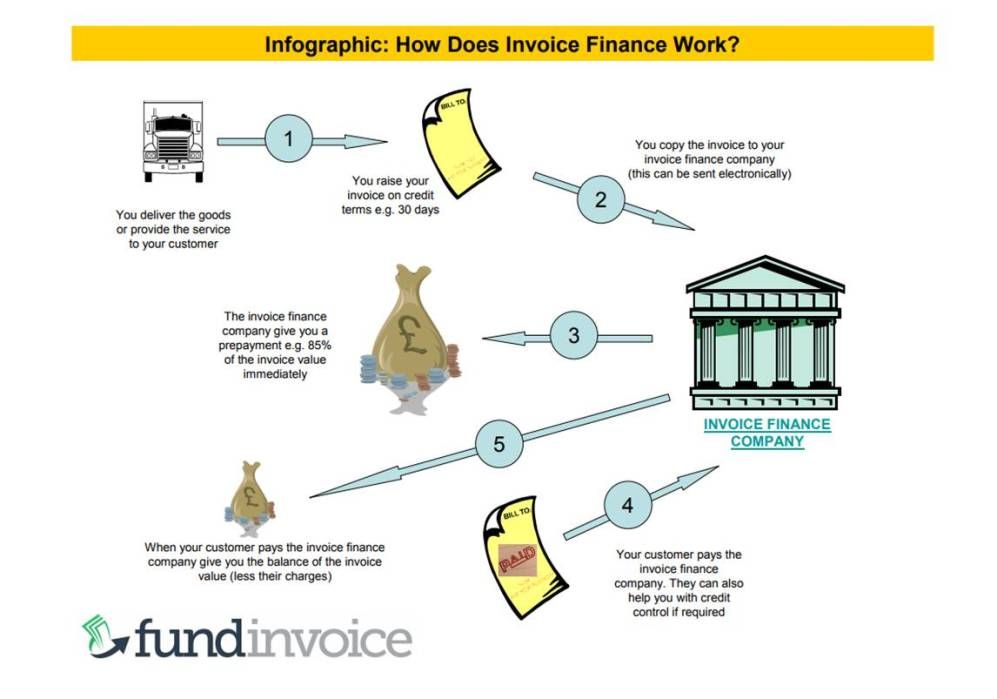

How finance works – Banks and other financial institutions differ significantly in their structure, ownership, and the services they offer. This section will explore the key distinctions between various types of institutions and the services they provide, highlighting the benefits and associated fees.

Types of Banks and Credit Unions

Banks and credit unions both offer financial services, but they operate under different structures and often serve distinct customer bases. Commercial banks are typically larger institutions offering a wide array of services to individuals and businesses, including checking and savings accounts, loans, and investment products. They are for-profit entities, aiming to maximize shareholder value. In contrast, credit unions are member-owned, not-for-profit cooperatives. They often focus on serving a specific community or group, typically offering lower fees and higher interest rates on savings accounts than commercial banks. Credit unions prioritize member benefits over profit maximization.

Functions of Various Financial Institutions

Beyond banks and credit unions, the financial landscape includes a variety of other institutions, each with specialized functions. Investment banks facilitate the issuance of securities, advise on mergers and acquisitions, and engage in proprietary trading. Insurance companies manage risk by providing coverage against various potential losses. Mutual funds pool money from multiple investors to invest in a diversified portfolio of assets. These institutions, along with others like brokerage firms and hedge funds, contribute to the overall functioning of the financial system.

Banking Services and Associated Fees and Benefits

The following list details common banking services, outlining typical fees and associated benefits. It’s important to note that specific fees and benefits can vary significantly depending on the institution and the individual account terms.

Understanding these fees and benefits is crucial for choosing the banking services that best suit your individual financial needs and goals.

- Checking Accounts: These accounts allow for easy access to funds through checks, debit cards, and online banking. Fees can include monthly maintenance fees, overdraft fees, and insufficient funds fees. Benefits include convenience, debit card access, and online bill pay.

- Savings Accounts: These accounts offer a safe place to store money and earn interest. Fees may include monthly maintenance fees or penalties for early withdrawals. Benefits include interest accrual, FDIC insurance (for accounts in FDIC-insured banks), and security.

- Loans: Banks offer various loans, including mortgages, auto loans, and personal loans. Fees can include origination fees, late payment fees, and prepayment penalties. Benefits include access to capital for large purchases or debt consolidation. Interest rates vary depending on creditworthiness and loan type.

- Credit Cards: Credit cards provide short-term borrowing and can build credit history. Fees can include annual fees, late payment fees, and interest charges on outstanding balances. Benefits include convenience, purchase protection, and rewards programs (such as cashback or points).

- Investment Services: Some banks offer investment services, such as brokerage accounts, mutual funds, and retirement planning. Fees can include brokerage commissions, management fees, and advisory fees. Benefits include access to investment products and professional financial advice.

Debt Management and Credit

Understanding debt and credit is crucial for navigating the financial landscape. Effective debt management can lead to financial stability and opportunities, while poor credit can significantly limit your options. This section explores the intricacies of credit scores, loan and credit card acquisition, and strategies for responsible debt management.

Credit Scores: Implications of Good and Bad Credit

A credit score is a numerical representation of your creditworthiness, reflecting your history of borrowing and repayment. Lenders use this score to assess the risk associated with lending you money. A good credit score (generally 700 or above) signifies a low risk, resulting in access to favorable loan terms, such as lower interest rates and better loan offers. Conversely, a bad credit score (below 600) indicates a higher risk, potentially leading to higher interest rates, loan denials, or less favorable terms. This can significantly impact your ability to secure loans, rent an apartment, or even obtain certain jobs. For example, someone with a good credit score might qualify for a mortgage with a 3% interest rate, while someone with a bad credit score might face a rate of 8% or higher, dramatically increasing the overall cost of the loan.

Obtaining a Loan or Credit Card

The process of obtaining a loan or credit card involves several key steps. Generally, you’ll need to submit an application, providing personal information, employment history, and financial details. The lender will then review your application, checking your credit report and score. If approved, you’ll receive a loan agreement or credit card contract outlining the terms and conditions. Different lenders have varying requirements and processes, but the core steps remain consistent. For instance, applying for a student loan might involve additional documentation from your educational institution, while applying for a personal loan might focus more on your income and debt-to-income ratio.

Strategies for Effective Debt Management

Effective debt management involves a proactive approach to repayment and responsible borrowing. Creating a budget to track income and expenses is fundamental. Prioritizing high-interest debts, such as credit card debt, through methods like the debt snowball or debt avalanche methods can significantly reduce the overall interest paid. Negotiating with creditors for lower interest rates or payment plans can also provide relief. Finally, avoiding unnecessary debt and building an emergency fund can prevent future financial difficulties. For example, using the debt avalanche method, which focuses on paying off the highest-interest debt first, can save you considerable money in the long run compared to the debt snowball method, which prioritizes paying off the smallest debt first.

Loan Application Process

The flowchart below illustrates the steps involved in applying for a loan.

Note: This is a general illustration and specific steps may vary depending on the lender and loan type.

Step 1: Complete the Loan Application. This involves providing personal and financial information, such as income, employment history, and credit history.

Step 2: Credit Check and Application Review. The lender will review your application and pull your credit report to assess your creditworthiness.

Step 3: Loan Approval or Denial. Based on the review, the lender will either approve or deny your loan application.

Step 4: Loan Agreement and Documentation. If approved, you will receive a loan agreement outlining the terms and conditions. You will need to sign this agreement and provide any required documentation.

Step 5: Loan Disbursement. Once the loan agreement is signed and all necessary documentation is received, the lender will disburse the loan funds.

Financial Planning and Goal Setting

Effective financial planning is crucial for achieving long-term financial security and fulfilling personal aspirations. It involves setting realistic goals, developing strategies to reach those goals, and regularly monitoring progress. This process empowers individuals to make informed financial decisions and build a secure future.

Setting Realistic Financial Goals

Setting realistic financial goals requires a clear understanding of your current financial situation, including income, expenses, assets, and liabilities. Goals should be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound (SMART). For example, instead of aiming to “save more money,” a SMART goal would be “save $5,000 in the next 12 months to fund a down payment on a car.” Breaking down large goals into smaller, manageable steps makes the process less daunting and provides a sense of accomplishment along the way. Consider using a budgeting app or spreadsheet to track progress and stay motivated.

Long-Term Financial Planning Methods

Several methods facilitate long-term financial planning. Budgeting is fundamental, providing a clear picture of income and expenses. This allows for identifying areas to reduce spending and allocate funds towards savings and investments. Developing a financial plan, often with the assistance of a financial advisor, involves setting specific financial goals, such as retirement planning, education funding, or purchasing a home. This plan Artikels strategies to achieve these goals, considering factors like investment options, risk tolerance, and time horizon. Regularly reviewing and adjusting the plan based on changing circumstances is vital for long-term success. Diversification of investments across different asset classes, such as stocks, bonds, and real estate, can help manage risk and maximize returns.

Retirement Planning and Investment Strategies

Retirement planning involves saving and investing money over time to ensure financial security during retirement. This requires considering factors such as retirement age, desired lifestyle, and expected lifespan. Several investment strategies can be employed, including contributing to employer-sponsored retirement plans (like 401(k)s or 403(b)s), investing in individual retirement accounts (IRAs), and diversifying investments across various asset classes. The specific strategy depends on factors such as risk tolerance, time horizon, and investment knowledge. For instance, younger individuals with a longer time horizon may be more comfortable investing in higher-risk assets like stocks, while those closer to retirement may prefer lower-risk investments like bonds. Regularly reviewing and adjusting the investment portfolio to align with changing circumstances and goals is crucial.

Sample Financial Plan for a Young Adult

The following table illustrates a sample financial plan for a young adult. Remember that this is a simplified example, and individual plans should be tailored to specific circumstances and goals.

| Goal | Timeline | Strategy | Estimated Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency Fund | 6 months | Save 3-6 months of living expenses in a high-yield savings account. | $3,000 – $6,000 |

| Pay off Student Loans | 3-5 years | Prioritize high-interest loans, explore refinancing options. | Variable, depending on loan amount and interest rate |

| Purchase a Car | 1-2 years | Save for a down payment, research financing options, consider used cars. | $5,000 – $20,000 |

| Start Investing | Ongoing | Contribute regularly to a retirement account (e.g., Roth IRA) and explore index funds or ETFs. | Variable, depending on investment choices and contribution amounts |

Understanding Financial Statements: How Finance Works

Financial statements are the cornerstone of understanding a company’s financial health. They provide a structured overview of a business’s performance, financial position, and cash flows, allowing stakeholders – including investors, creditors, and management – to make informed decisions. Analyzing these statements effectively requires understanding their individual components and how they relate to one another.

Balance Sheet Components, How finance works

The balance sheet presents a snapshot of a company’s assets, liabilities, and equity at a specific point in time. It adheres to the fundamental accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity. Understanding each component is crucial for interpreting the overall financial health.

Income Statement Information

The income statement, also known as the profit and loss (P&L) statement, reports a company’s financial performance over a specific period, such as a quarter or a year. It summarizes revenues, expenses, and the resulting net income or net loss. Analyzing this statement reveals trends in profitability and operational efficiency.

Cash Flow Statement Interpretation

The cash flow statement tracks the movement of cash both into and out of a company over a period. It categorizes cash flows into operating activities (day-to-day business), investing activities (acquisitions and investments), and financing activities (debt and equity). A step-by-step approach to interpreting this statement helps assess liquidity and solvency. First, examine the cash flow from operating activities to determine the cash generated from the core business. Next, analyze investing activities to understand capital expenditures and investment returns. Finally, review financing activities to see how the company is funding its operations and growth.

Illustrative Balance Sheet

| Assets | Liabilities | Equity |

|---|---|---|

| Current Assets: These are assets that can be readily converted to cash within a year, such as cash, accounts receivable (money owed to the company), and inventory. | Current Liabilities: These are obligations due within a year, such as accounts payable (money owed by the company), salaries payable, and short-term debt. | Shareholders’ Equity: This represents the owners’ stake in the company, including retained earnings (accumulated profits) and contributed capital (money invested by shareholders). |

| Non-Current Assets: These are long-term assets, such as property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), and intangible assets like patents or trademarks. These assets are not easily converted to cash. | Non-Current Liabilities: These are long-term obligations, such as long-term debt and deferred revenue (revenue received but not yet earned). |

Inflation and its Impact

Inflation represents a general increase in the prices of goods and services in an economy over a period of time. When the price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services. Consequently, inflation reflects a reduction in the purchasing power per unit of money – a loss of real value in the medium of exchange and unit of account within the economy.

Inflation’s causes are multifaceted and often intertwined. Demand-pull inflation occurs when aggregate demand outpaces aggregate supply, leading to increased competition for limited resources and pushing prices upward. Cost-push inflation, on the other hand, stems from increases in production costs, such as wages or raw materials, which businesses pass on to consumers in the form of higher prices. Government policies, particularly excessive money supply growth, can also contribute significantly to inflationary pressures. Supply shocks, such as unexpected disruptions to resource availability (e.g., oil price spikes), can also trigger inflation.

Inflation’s Effect on Purchasing Power

Inflation directly erodes the purchasing power of money. A fixed amount of money will buy fewer goods and services as prices rise. For example, if inflation is 3% annually, an item costing $100 today will cost approximately $103 next year. This reduction in purchasing power disproportionately affects individuals on fixed incomes or those with savings in low-yielding accounts, as their real wealth diminishes over time. This impact is particularly noticeable in periods of high inflation, where the loss of purchasing power can be substantial. Careful financial planning and investment strategies are crucial to mitigate this effect.

Strategies for Mitigating Inflation’s Effects

Several strategies can help individuals protect their finances from inflation’s erosive impact. Investing in assets that tend to appreciate in value alongside or faster than inflation, such as stocks, real estate, or inflation-protected securities (like TIPS – Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities), is a key approach. Diversification across different asset classes reduces risk and helps maintain purchasing power. Regularly adjusting savings goals and investment allocations to account for anticipated inflation is crucial for long-term financial security. Increasing income through salary negotiations, additional employment, or entrepreneurial ventures can also help offset the impact of rising prices. Finally, monitoring spending habits and identifying areas for cost reduction can provide additional financial resilience.

Inflation’s Impact on Money Over Time

The following table illustrates how inflation affects the value of money over a five-year period, assuming various inflation rates and an initial investment of $10,000. These are hypothetical scenarios and actual results may vary.

| Year | Inflation Rate | Initial Value | Value After Inflation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 2% | $10,000 | $9,803.92 |

| 2025 | 3% | $10,000 | $9,708.74 |

| 2026 | 4% | $10,000 | $9,615.38 |

| 2027 | 5% | $10,000 | $9,523.81 |

| 2028 | 0% | $10,000 | $10,000.00 |

Tim Redaksi